|

Helen Roberts, born in 1877, recorded some fascinating memories of her childhood whilst living in Deverell Cottage, Westbrooke (opposite Sion Junior School). After moving from Deverell Cottage, she became friends with the new occupier, a Maida Butler and it was Maida's niece, Mrs Beatrice Longhurst, who has graciously lent me these Victorian memoirs. Helen wrote: -

Colours, as well as scents, can induce nostalgia, in a stock phrase 'conjure up the past'. But this is white magic, natural and happy, something we would never wish to be without. Just as I cannot think of a garden without its long-lived fragrance of sweet briar, when I remember the dining room, the word - the operative word as they say now - is terracotta. For it was a terracotta age, and, though we ourselves couldn't remember any other, it is certain that, to our elders, this fag-end of the eighties (1880's) was a period of curious and almost exotic new fashion.

Gone now from carpets and hangings were the gas greens and royal blues, the solferino and magenta ribbons that had brightened my mother's childhood.

There was an opera called 'Patience' which had taught us to adopt as well as to smile, at 'greenery-yallery' tints. There was a critic called Wilde, a pioneer and a boon to home decorators called Aspinall, there were bullrushes, peacocks feathers, smocked pinafores, Japanese fans and silks, and a fine new shop in Regent Street where all these things could be bought.

But Terracotta, in its tangible form, was much about us in those days. Ferns in terracotta pots dangled in the greenhouse. A terracotta bust of Mr Gladstone, my father being a good Liberal, gazed sternly out between our trick money boxes in the billiard room, while a group reproduction in terracotta, of the cherubs from Raphael's Sistine Madonna (we called them, affectionately, 'Little Boy and his Sister') had the place of honour on the drawing room wall.

So our dining room was inevitably coloured like the good earth, and we were its curtains, its carpet, and its ample tablecloth of 'art serge'.

The room was belted three parts down its length with an oaken band, and the lower portion clad in Japanese paper, in which a deeper terracotta was merged in a dim flower pattern with brown and old gold. This part of the wall, we were told, was called a dado, a word pleasing to us. We knew a little girl in Victoria Road who had a dog called Dado, and the word sounds, and seems to me still, so pleasantly doggy that it might almost wag its tail at you.

Opposite the graceful double windows in the dining room stood the sideboard, with carved plums on one side and pears on the other. On a shelf above was a shining row of cups and mugs, won by my father for swimming and rifle shooting. Oil paintings hung on the walls - a Surrey common, a Welsh mountain, Hastings at sunrise, yet all so much alike that they must have been the work of one hand.

My father's favourite pictures, his peculiar treasures, hung in his dressing room, where they covered two walls. The drawings and photographs were of his little sailing boats - the Grebe, the Wave, the Fleet-wing, the Kittiwake, the Mayfly, one and two, the Kelpie, the Bluette, The Red Spinner, and others. As he was never quite satisfied with their paces, he sold the old one and bought a fresh one every spring, for which reason he was known to all his friends as 'The Skipper'.

He did not often take us out in his boats, because some of them had rather a tendency to capsize. When he did, however, he was careful to tie a brightly striped, inflated collar round our necks. Inevitably, we felt, even it we did not look, like Tom in 'The Water Babies' when he found an undetachable rainbow ruff just below his ears. To know precisely, how my parents looked when, in fair weather, they went sailing together, one has only to glance at Manet's 'Boaters' in the Museum at Tournai.

The books in the dining room, like the cups on the sideboard, could not be removed by us. We had books of our own, of course, but far too few, and I look with envy at the children of today with their own tickets into their own departments at the libraries.

On the little shelf above my bed I kept 'Alice', 'Lamb's Tales', 'What Katy Did' and 'The Cuckoo Clock', but I had read them over and over again.

There remained, however, the big ramshackle bookcase in the parlour, which was free to all who came. Beside our lesson books, there were a number of works about cookery and household management. 'Mother's Guides' and so forth. These I read with a moderate amount of pleasure.

But when I was older and taller, I discovered better mater on the top shelf, which was chock full of books, then called 'yellow backs' (two shillings, with gay picture covers). They must have been invented, in my present guess, by Messrs Chatto and Windus in the sunny eighties, for the edification of the common man, the common woman and the common child.

Nursie, Eliza and silly Aggie (the housemaid) also had recourse to this shelf, and a purloined Miss Braddon might be seen in the stocking basket and a Mrs Hungerford in the pantry drawer.

For myself I found Lady Audley too long in disclosing her secret, though I could enjoy the blushes and tears of Whyte-Melville. It was Ouida, a little later, who came, a dazzlement, playing Chapman to my Keats. There was 'Puck', 'Chandos', 'Tricotrin' and 'Othmar'. I did not read them exhaustively, but wandered, confusedly, in tracts of them all, puzzled, bewitched by some new quality - strange limelight that never as on sea or land. Glamour? That now threadbare word was unknown to Victorians, but I could not persuade my sisters to try these new pastures.

With a mere glance at the French exclamations, the Italian place names, the Russian princes, they rejected my discoveries, and returned to 'Tom Brown's School Days' and 'Swiss Family Robinson'. Their taste, I regret to say, was sounder and less bizarre than my own.

Although my parents were not Puritans or Podsnaps, we were living then not far below the peak hour of Evangelical supremacy, when it was impossible for any middle class child to escape altogether from sermonising and exhortation. Nursie and Miss Warner were both ready with cautionary tales, stout ladies in drapers' shops would ask us, dubiously, if we were saved, and even on the beach we were sometimes persuaded by members of the Salvation Army to join them in hymns and intercessions for such sinners as ourselves. At times this depressed me a little.

So I have good reason to remember, with gratitude, a certain Sunday evening when our book was 'Ivanhoe', and our chapter, that which describes the death of Front-de-Boeuf in his castle of Torquilstone. It is a magnificent chapter, and my father had probably let himself go in a manner worthy of Sir Walter's genius.

You might suppose that when the Norman miscreant lies groaning, already in the throes of death from an axe stroke on the skull delivered by Coeur-de-Lion himself, while victorious Saxons splinter helms and crash posterns all about him, that a climax had been reached. Yet there is worse - or better - to come.

For now the avenging and maniacal Ulrica is at his bedside to exchange her curses with his. 'Foul parricide, and vile blasphemer!' she shrieks, or croaks. 'Markest thou the smouldering and suffocating vapour which already eddies in sable folds through the chamber? Didst thou think it was but the darkening of thy bursting eyes? No, Front-de-Boeuf, there is another cause. Rememberest thou the magazine of fuel that is stored beneath these apartments?'

So he was burnt, with all his gear and all his victims and all his vassals, till there was nothing else to lose and it was time to shut the book and prepare for bed.

At this point it was usual for Mia, Mab and I to talk all at once, but tonight we sat quiet as mice, awed, scarcely daring to move, though conscious, too, that we should like to take hold of somebody's hand, or get inside somebody's elbow. We were not sure either that we should much like going up the dark staircase, and remembered the night-light in a saucer, discarded years ago. Perhaps on this evening we could have the gas not quite turned out - just a little blue bead left?

At last Mia said from the rug, 'Did Front-de-Boeuf go to Hell? I rather think he did. He was such an uncommon, bad lot.' 'How bad must a person be,' asked I, 'before he can go to Hell? Would he have to kill his father, like Front-de-Boeuf? Would he have to do a murder?' 'Oh yes, he would certainly have to do one or two murders before he could get in there', was the reply.

So my obsessions were dispersed. And by an infallible authority. Nursie had a rhyme, which said that if you fight and scratch and bite, then well you know where you will go. But, as our tempers were fairly even, we hadn't even gone in for scratching and biting. And murder? We hadn't the pluck. We hadn't the tools. It was a passport we should never gain. If fifty pounds had been spent on my behalf with a psycho-analyst, I could not have been in better trim.

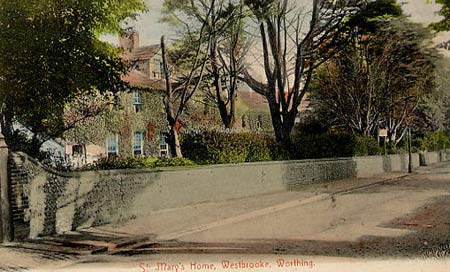

A late Victorian view in the road called Westbrooke.

| |