|

Pat Smyth, a civil servant with the National Assistance Board in West Tyrone from the 1930's to the 1950's, recalls his memories, experiences and the larger than life personalities he encountered on the way.

Some of the older people in Tyrone called the old age pension officer, the 'Gauger', a relic of the days when pensions were administered by the Excise Department. In the early days of old age pensions, the big wind of 1839 was used as a kind of benchmark for claimants who had no other evidence of age.

Births were not always registered in the nineteenth century, and only a minority of poor children got any schooling. Christian baptism was not universal either. Some denominations just did not bother. School roll books in remote areas were often a 'dog's dinner'.

Very often claimants got older neighbours to swear to their age. In sticky cases, pension officers tended to play safe and disallow claims, leaving claimants to appeal to a tribunal. At an oral hearing, with sworn affidavits, evidence was sifted and final decisions made.

In the case of smallholders the real or potential labour value of the claimant was crucial. With the aid of agricultural advisers, a figure had been fixed, as the profit to be levied on each acre of crop, and each head of cattle, sheep and poultry.

This was based on the assumption that all the labour needed had to be hired. The pension officer had first to get a signed statement of all the stock and acreage's of crop on the smallholding. Then he had to tour the place and make a check. A man, especially a 'townie' who didn't know a rood from an acre, was no match for a wily small farmer.

Not being in that category myself I was able for most of them, and when they took me to see the one-and-a-half acre plot from which a crop of potatoes had been harvested I very often found the plot to be more like two-and-a- half acres and made a challenge. The claimant would quickly come up with the excuse - 'Ach! I grew a wee lock of turnips and cabbage as well, mister I forgot to mention them'

Having got the stock counted and the acreage of grazing, hay, potatoes, oats and maybe flax, settled, the pension officer had to do his homework, using the profit figures given in his code, bearing in mind that these figures were based on the assumption that all the labour had had to be hired.

Crofters in Tyrone did not hire labour; hence the profits to be charged nearly always had to be augmented by the value of the (unpaid) labour done by the claimant, his wife and/or family.

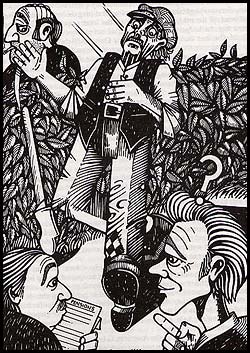

'Galloping senility' by Niall Dynes.

A precedent was set on one historic occasion when a mountain family convinced an appeal tribunal that £x of labour needed for sheep raising was done by two well-trained sheep dogs! This was fair enough. Obviously the man of seventy's capability for tending a large flock on a mountain was limited. There was no help hired, and none within the household. The old man won his case, and blazed a trail for many others, following an Umpire's ruling.

All these regulations had to be observed by anyone wishing to claim a pension. They produced amusing episodes such as the one that I witnessed when I accompanied Stanley Thomas, the long experienced Omagh pensions-officer of the pre-war years, on a run in the Fintona area one October day in 1948.

A few years after the war ended the Board was made responsible for assisting anyone in need, and the administration of the means-tested old age pension scheme became my responsibility.

Stanley Thomas of the Ministry of Labour was the pension officer and at the hand-over stage he invited me to accompany him on his rounds. One day we headed out of Fintona, past the gold links (where an historic fairy thorn had stood) and away towards Fivemiletown. We had a right pantomime.

The man we were looking for wasn't at home, but we got clear directions where to find him, and as we went down the road everyone we asked was able to tell us exactly where we would find him, which was a bit strange in Tyrone.

The last ones we asked were two lads coming from school, who told us he was around the next bend in the road. As we left them one of them shouted 'And he hasn't the hedge cut yet, Mister'. This puzzled us but we motored on.

When we got round the bend, we found a group of men armed with saws, billhooks and farm graips, busy removing a roadside hedge. They paid little heed to us for a few minutes. Then the eldest threw down his billhook and came over to us. 'Another hour, or better, will do us', he remarked.

Stanley was a bit nonplussed, but he made encouraging noises and some small talk. Suddenly, as the man turned to resume his toil, Stanley introduced himself. As soon as he heard the words 'pension officer' the man blanched and I have never since seen anyone so suddenly afflicted by galloping senility and feebleness!

He told Stanley he felt he was about to have a heart attack - that he must have overdone it and he staggered over to the farm cart parked nearby, and painfully lowered himself to a seat on the shaft.

Stanley showed no surprise, but proceeded to ask the usual questions. Then he asked his man if it would be convenient for him to get into the back of the car and accompany us back to his home so that Stanley could see his birth certificate and 'rent paper' of the farm and so on.

Only then did the penny drop! The old boy explained that 'Glasgow' (the County Surveyor) had taken him to court for not cutting the hedge, which obscured a bad bend on the road, used regularly by the local aristocrats. The court had ordered that the hedge should be cut within seven days and the deadline was 4.00 p.m.! Our man thought we were County Council officials!

'Nothing very strange so far' you may well remark, but this is the crunch. When a farmer claimed the old age pension in those days, there was a very tight means test, and the success or failure, of the claim depended a lot on the amount of labour that the man claiming the pension was doing on the farm himself.

If he was as fit as my farmhand and there were enough animals and crops on the place to keep him busy, then he had no chance. If this claimant with the big hedge had known that the pension officer was coming, he would probably have been hobbling around on two sticks, or maybe laid up in bed, certainly not wielding a billhook!

For how the heck does a man who has been seen leading the team, and showing the other boys how to cut a thorn hedge, set about convincing a pension officer, who has seen his prowess, that his own labour value on his farm is nil or negligible?

Pat Smyth, 2001

| |